Introduction

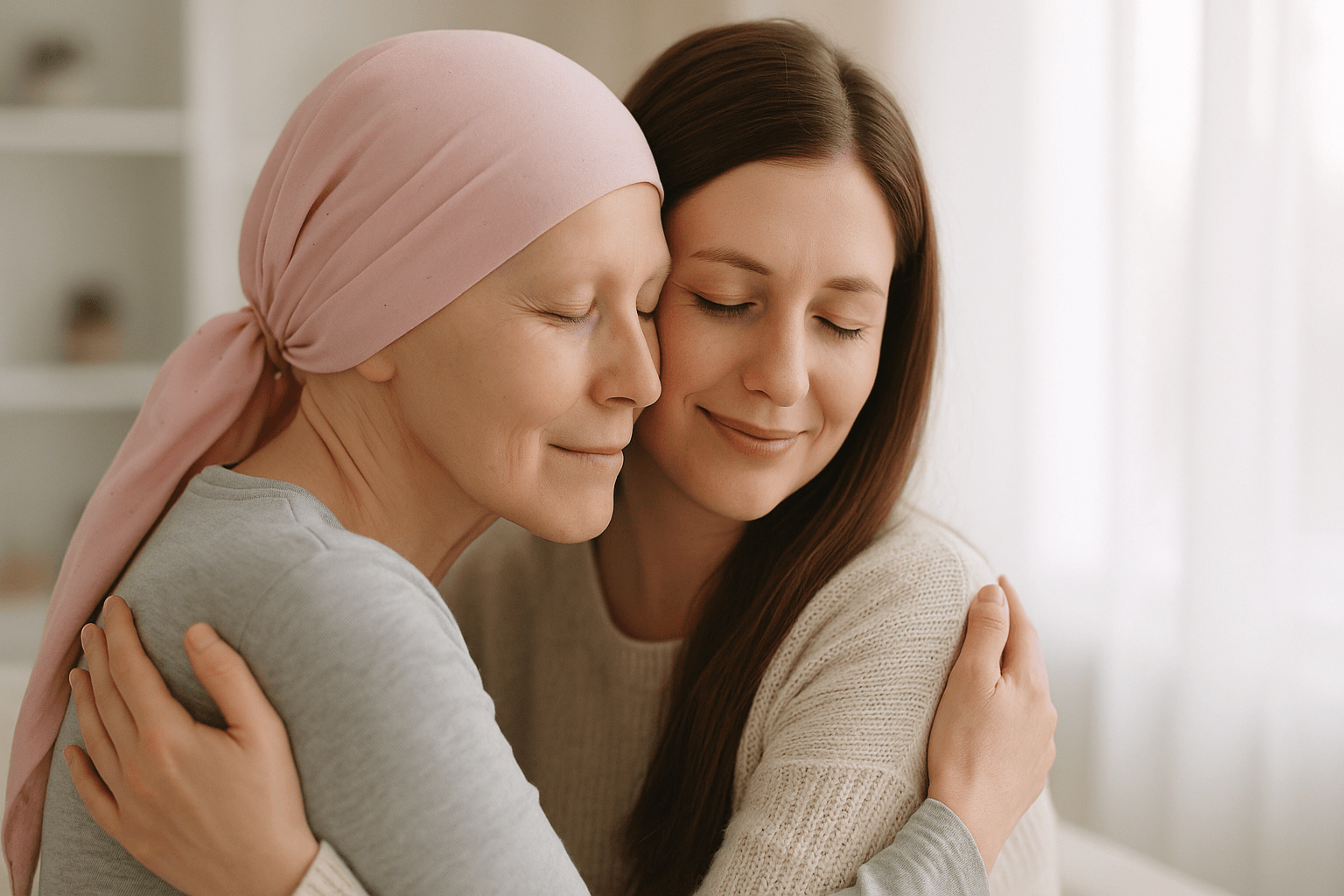

Can an emotional state really impact our physical health? Increasingly, research suggests the answer is yes. One striking example is the connection between unforgiveness, the state of holding onto resentment, anger, or bitterness, and serious illnesses such as cancer. Some medical experts now even refer to unforgiveness as a disease in itself, given its toxic effect on the body and mind. Dr. Steven Standiford, Chief of Surgery at the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, bluntly states that refusing to forgive makes people sick and keeps them that way. With this understanding, a new approach known as forgiveness therapy is emerging as a component of treatment for patients battling disease, including cancer.

One eye-opening statistic highlights why addressing unforgiveness is so important in health care. Among cancer patients, 61 percent have issues with forgiveness, and of those, more than half are severe. Doctors like Dr. Standiford believe this is no coincidence. It is important to treat emotional wounds or disorders because they really can hinder someone’s reactions to the treatments, even someone’s willingness to pursue treatment. In the battle against cancer, unhealed emotional pain may be an unseen obstacle to healing.

Modern medicine is beginning to acknowledge what many traditions have long hinted, that the mind and body are deeply interconnected. Studies have found that the act of forgiveness can reap significant rewards for health, improving everything from heart health and sleep quality to stress levels and immune function. Conversely, dwelling in chronic anger and resentment can keep the body in a state of high stress, weakening its defenses. This article explores how unforgiveness can affect adults with cancer, examines why letting go of grudges is vital for healing, and discusses how forgiveness therapy is being used as a holistic strategy to improve patients’ emotional and physical well-being. We look at emerging research, share insights from experts, and consider the emotional and psychological impacts of forgiveness, all pointing to a powerful conclusion. Forgiveness may be as important to health as any medicine.

Unforgiveness and Physical Health: The Hidden Disease

When we talk about unforgiveness, we mean a persistent state of resentment, anger, or hostility toward someone, including oneself, due to a perceived wrong. It is the inability to let go of a grudge or heal from a hurt. Living in this state places a heavy burden not just on our mood but on our physical health. Chronic unforgiveness creates a state of prolonged stress and anxiety in the body. Medical researchers have likened this to a disease process because of how clearly it can undermine health.

Physiologically, unforgiveness often translates into chronic stress. When you recall a deep hurt or actively harbor anger, your body reacts as if under threat. The fight or flight response is triggered, releasing stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol into your bloodstream. Holding onto anger essentially creates a perpetual fight or flight state. Over time, elevated levels of adrenaline and cortisol take a toll. They can damage blood vessels, raise blood pressure, and suppress the immune system’s function in subtle but significant ways.

One of the critical impacts of chronic stress from unforgiveness is on the immune system. When the body is busy producing stress hormones to deal with emotional turmoil, it may divert energy away from important functions such as immune response, cell repair, and even digestion and sleep. Under the influence of cortisol, the production of certain white blood cells is inhibited. Notably, research indicates that chronic anxiety from unresolved anger produces excess adrenaline and cortisol, which in turn deplete the production of natural killer, NK, cells, the very cells your immune system deploys to combat cancer. In simple terms, staying bitter can weaken the body’s natural defenses.

The damage of unforgiveness is not limited to the immune system. Long-term anger and stress have been correlated with a host of health problems. Studies have linked chronic anger or unforgiveness with an increased risk of conditions such as heart disease and hypertension, elevated risk of heart attacks, chronic pain and tension headaches, arthritis, gastrointestinal problems such as ulcers and irritable bowel syndrome, and metabolic and immune-related disorders including insomnia and diabetes. The gut, sometimes called our second brain, is extremely sensitive to stress hormones.

This list is a stark reminder that the high cost of unforgiveness can be paid in degraded physical health. When we carry bitterness, it is our bodies that bear the brunt of that burden. On the flip side, choosing to forgive can reverse many of these ill effects. A growing body of scientific research shows that forgiveness offers significant health benefits. For example, studies have found that people with forgiving personalities enjoy better psychological well-being and fewer physical health symptoms. They tend to use less medication and report fewer aches and illnesses. Other studies have found that forgiveness is associated with better sleep quality and less fatigue in daily life, likely because a mind at peace can rest more easily.

Physical measurements of the effects of unforgiveness versus forgiveness are particularly revealing. In one experiment, researchers asked volunteers to revisit hurtful memories and grudges while measuring their blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tension, and sweat gland activity. As expected, simply thinking unforgiving thoughts caused participants’ blood pressure to spike, heart rate to increase, facial muscles to tense, and perspiration to rise, clear signs of a stress response. But when those same people were guided to imagine granting forgiveness to those who wronged them, their bodies responded very differently. Forgiving thoughts prompted greater perceived control and comparatively lower physiological stress responses. In other words, forgiveness led to lower blood pressure and more relaxed muscles, essentially calming the body’s alarm systems. The researchers concluded that chronic unforgiving responses may erode health, whereas forgiving responses may enhance it.

Given these findings, it becomes clearer why some physicians speak of unforgiveness itself as an undiagnosed disease. When Dr. Standiford says unforgiveness is classified in medical books as a disease, it reflects this understanding that a continued state of bitterness can manifest as physical illness. From clogged arteries to weakened immunity, the fallout of unresolved anger is profound. The good news is that forgiveness, often thought of as a purely moral or religious act, turns out to be a potent medical act as well. By releasing resentment, we not only free the mind but also liberate the body from the toxic stress that was quietly sabotaging health.

The Emotional and Psychological Toll of Unforgiveness

Unforgiveness does not only hurt the body, it wreaks havoc on the mind and spirit. Carrying long-term anger or resentment is like carrying a heavy rucksack full of rocks everywhere you go. It weighs you down, saps your joy, and can eventually lead to serious psychological strain. Mental health professionals note that people who hold onto grudges often experience higher levels of anxiety, stress, and depression. In contrast, those who are more forgiving tend to be happier and emotionally healthier.

Psychologically, living in a state of unforgiveness often means ruminating on the wrong that was done. People replay the hurtful events in their minds, relive the anger, or fantasize about revenge or vindication. This constant rumination can fuel feelings of bitterness, irritation, and sadness. Over time, such patterns can contribute to chronic anxiety disorders or depressive episodes. Some studies have shown that individuals who hang on to grudges are more likely to experience severe depression and even symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder compared to those who practice forgiveness. A national survey found that many adults feel they need more forgiveness in their lives, suggesting that people recognize they are stuck in states of unresolved conflict or resentment that harm peace of mind.

On the flip side, cultivating forgiveness has notable psychological upsides. Forgiveness is often described by those who experience it as deeply liberating. Many patients report that once they truly forgave someone who hurt them, they felt as if a weight was lifted from their shoulders, sometimes describing a feeling of lightness or relief that they had not felt in years. Forgiveness helps break the cycle of rumination and resentment. Instead of constantly dwelling on negative feelings, a forgiving mindset replaces those with more positive, healing emotions, such as empathy, understanding, and even compassion toward the offender. Psychologically, this shift from a negative to a positive emotional state can reduce stress and promote a sense of inner peace.

It is important to clarify that forgiveness is not about condoning the wrong or saying that the hurtful behavior was acceptable. It also does not mean you must forget what happened or reconcile with the offender if that is not safe or feasible. Rather, psychologists define forgiveness as a conscious decision to release feelings of resentment or vengeance toward someone who has harmed you, and to make peace with the situation. As Dr. Frederic Luskin puts it, forgiveness means that even though what happened is not okay, you can move on and make peace for yourself. It is essentially an act of self-healing. You are freeing yourself from the mental prison of bitterness. You stop allowing that past hurt to control your mood and outlook. This reframe often brings a powerful sense of control back to the individual’s life. They are no longer emotionally at the mercy of the past offense.

The emotional benefits of forgiveness are backed by research. People who learn to forgive often experience reduced anxiety and anger, as well as fewer symptoms of depression. They tend to report greater life satisfaction and optimism. In everyday life, someone who is forgiving will likely cope with stress better and have more positive relationships, because they are not easily trapped in cycles of blame and bitterness. By contrast, someone mired in unforgiveness may find it affects their relationships with others too. They may be irritable, less trusting, or socially withdrawn because of their preoccupation with past wrongs.

Unforgiveness can even become a chronic mindset if it goes on too long. A person can become the victim in their own narrative, defining themselves by how they were hurt. This often leads to ongoing feelings of helplessness or rage that are psychologically corrosive. Forgiveness, conversely, empowers the individual to rewrite that narrative. They are no longer just a victim, but a survivor who has taken their emotional power back. This empowerment is why forgiveness is often accompanied by an increase in self-esteem and hope. In cancer patients and others facing life challenges, regaining hope and emotional strength is critical.

The Link Between Unforgiveness and Cancer

A cancer diagnosis is not just a physical ordeal, it is an emotional and spiritual journey as well. Patients often confront intense feelings, fear, loss, anger, guilt, and regret, as they navigate their illness. Unforgiveness is strikingly common among cancer patients, and this may have implications for both quality of life and possibly disease progression. Research indicates that about 61 percent of all cancer patients have significant forgiveness issues, and more than half of those are severe. That means a large proportion of people fighting cancer are also fighting an inner battle with anger, whether it is anger toward others, themselves, or circumstance.

For many patients, cancer acts as a mirror that forces reflection on life and relationships. Studies of survivors show that a diagnosis can trigger people to revisit past grievances or hurts. Common scenarios include anger at others, such as a family member who was not supportive, anger at oneself, such as self-blame for delaying checkups, and anger at fate or a higher power. In interviews with cancer patients, persistent self-blame was common and linked to deep emotional pain. Notably, patients who were able to find self-forgiveness coped more positively. Forgiving themselves contributed to managing the disease in a healthier way and gave them strength to move forward.

Beyond the emotional impact, a physical link is plausible through the stress pathway. Cancer is intertwined with immune function. Chronic stress impairs immunity, including natural killer cell activity. Unforgiveness can hamper recovery by keeping patients in a physiological state that is counterproductive to healing. Excess adrenaline and cortisol, fueled by anger and anxiety, can depress immune defenses against cancer cells. If a patient is burdened with severe unforgiveness, their immune system may be weakened, potentially giving cancer a foothold it might not otherwise have.

Unforgiveness can also influence how patients respond to treatment. Cancer therapies are physically taxing and require commitment. Depression or chronic anxiety from unresolved anger can sap energy and hope, sometimes affecting willingness to pursue treatment. Emotional wounds can hinder reactions to medical care, for example, by disrupting adherence to medication schedules or lifestyle recommendations. In contrast, patients who find emotional peace often engage more proactively in their care. Healing emotional pain can enhance the effectiveness of physical healing.

Quality of life is another key factor. A person with cancer who also carries anger and grudges suffers doubly, physically from disease and emotionally from bitterness. Psychological stress can worsen pain perception, sleep, and fatigue. Interventions that promote emotional healing, such as forgiveness work, have been linked to improvements in well-being. In one study with terminal patients, a short forgiveness intervention significantly improved quality of life, even as physical health declined.

Early indications suggest forgiveness might not only improve how patients feel, but could possibly influence disease trajectories in select contexts. Case reports in low-grade multiple myeloma describe disease stabilization after structured forgiveness therapy. These are preliminary observations, not proof of cure, yet they suggest that by reducing stress and inner turmoil, the body’s defenses and repair mechanisms may function better. Ongoing work aims to measure this rigorously, including immune markers that could reveal how forgiveness practices support resilience in cancer care.

There is also an existential dimension. Many people with cancer struggle with the question, why me. Anger at life or God for the misfortune of illness can lead to despair. In this context, forgiveness means finding a way to make peace with what cannot be controlled. Patients who reach acceptance often report reduced emotional suffering. They may not like what happened, but they no longer rage against it internally. This resolution can restore a sense of spiritual peace that is invaluable when coping with a life-threatening illness.

Forgiveness Therapy in Cancer Care: A Holistic Healing Approach

To meet the intertwined physical and emotional challenges of cancer, many providers use holistic approaches that address the body, mind, and spirit. One such approach is forgiveness therapy. It guides individuals to confront and let go of deep-seated resentments and grudges and is used as a complementary treatment in cancer care.

At the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, spiritual and emotional support is integrated with oncology. Based on the recognition that emotional wounds can hinder treatment, forgiveness interventions have been incorporated into care models. One program designed by Rev. Dr. Michael Barry was brief by design so it could fit the realities of treatment schedules. A common structure includes focused counseling and education, short reflective writing assignments, and follow-up processing with a clinician.

A key technique is expressive writing, adapted from trauma disclosure research. Patients write privately about their hurt for several short sessions in a day or two. They are encouraged to be candid about feelings and to notice irrational thoughts that keep anger alive. Bringing these to light allows reframing. For example, shifting from nobody cares about me to I have people who can support me, or from that person ruined my life to I will not give that person power over my future. This cognitive shift opens the door to forgiveness.

Another cornerstone is developing empathy or humane understanding for the offender. This does not excuse wrongdoing. It acknowledges the offender’s humanity and context, which can diffuse the emotional charge that sustains a grudge. Secular models, such as those by Robert Enright and Richard Fitzgibbons, often move through four phases. Uncovering, decision, work, and deepening. Patients examine the costs of anger, choose forgiveness, practice empathy and reframing, then integrate new meaning and resilience.

Forgiveness therapy is voluntary and paced to the individual. No one should be pressured to forgive quickly or superficially. Many patients also work on self-forgiveness, which is vital when guilt or self-blame is present. For those with religious commitments, faith practices can be woven in. For others, the focus remains secular and health centered. The goal is the same. Help the person release toxic resentment that impedes healing.

Outcomes reported from forgiveness interventions include improved mood, reduced anger, better sleep, and, in some studies, favorable changes in cardiovascular measures such as blood pressure and blood flow. These point to a plausible physiological pathway by which forgiveness lowers stress burden and supports healing. In cancer care, the practical benefits are clear. A calmer, more hopeful patient is more likely to participate fully in treatment and self-care.

Benefits of Forgiveness: Healing Body and Soul

Forgiveness offers tangible benefits that matter for anyone, and especially for those facing cancer.

Reduced stress and anxiety. Letting go of grudges lowers cortisol and adrenaline, which can reduce blood pressure and heart rate. Laboratory studies show calmer cardiovascular responses during forgiving thoughts. Over time, less stress means less wear and tear on the body.

Improved mental health and mood. Forgiveness is linked to lower depression, less chronic anger, and higher levels of hope and self-esteem. Patients often describe feeling lighter and more peaceful after forgiving.

Stronger immune function. Lower stress can support immune activity, including natural killer cells and T cells. For cancer patients, any improvement in immune surveillance is valuable.

Heart health and lower blood pressure. Chronic anger harms the heart. Forgiveness is associated with lower blood pressure and better cardiovascular function. Clinical programs have demonstrated improved cardiac measures after forgiveness work.

Better sleep and pain management. A quieter mind sleeps better. Relaxation linked to forgiveness can ease muscle tension and reduce pain reports, which supports recovery.

Enhanced relationships and social support. Letting go of bitterness often repairs or softens relationships. Stronger support networks are protective during illness.

Spiritual and emotional peace. Many find alignment with personal values or faith through forgiveness, reducing existential anxiety and restoring meaning and calm.

These benefits underscore a simple point. Forgiveness is not only a noble virtue, it is a practical health strategy. No pill can replicate its broad effects. It comes from inner work that anyone can begin.

Conclusion

Unforgiveness can poison health, while forgiveness can powerfully heal. Left unresolved, emotional grievances can spiral into physical stress, weakened immunity, and a range of health problems. For adults with cancer, carrying the extra burden of anger or resentment is especially harmful. The finding that a majority of cancer patients struggle with forgiveness highlights the need to address emotional wounds alongside physical treatment.

Forgiveness therapy offers hope by helping patients release grudges and find peace. Evidence indicates improvements in stress markers, immune function, blood pressure, sleep, and overall quality of life. It can rekindle emotional resilience and a will to live. Choosing to forgive is not about excusing harm. It is about safeguarding your own health and sanity. Holding onto anger harms us. Forgiveness is the antidote. It is not easy, but the rewards are immense.

The future of cancer care is not only smarter drugs. It is also care for the emotional and spiritual needs of patients. Integrating forgiveness into support programs strengthens the whole person. For anyone on a healing journey, do not overlook the power of forgiveness. Seek support if you need it. Talk to a counselor, join a group, or draw on your faith. Healing is not always about cure. Sometimes it is about becoming whole. Forgiveness can be a path to that wholeness.

References

A Healthier Michigan. 2015. Could Forgiveness Improve Your Health. https://www.ahealthiermichigan.org

Belmont Abbey College. 2025. Forgiveness Therapy, research overview and program outline. https://www.belmontabbeycollege.edu

Boleková, V. 2024. Predictors of forgiveness in cancer patients after treatment. Health Psychology Report, 12, 219–226. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Cancer Treatment Centers of America, statements attributed to Steven Standiford, MD. Coverage archived by CBN News. https://www.cbn.com

International Forgiveness Institute. 2018. The Amazing Benefits of Forgiveness Therapy on Cancer Patients. https://internationalforgiveness.com

Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2020. Forgiveness, Your Health Depends on It. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org

Luskin, F. The Art of Forgiveness, Stanford Medicine, Surviving Cancer. https://med.stanford.edu

Science Times. 2019. Science Says that Forgiveness is the Path to a Healthy Body. https://www.sciencetimes.com